Our Institute

Clinical Trials

Our Science

News

International Patients

- International Patients

- International patient Service Care

- Travel Arrangement and Hospital Admission

- FAQ

- Contact Us

弥漫内生性脑桥神经胶质瘤(DIPG)或是脑胶质瘤(GBM)是一种广泛浸润性的恶性肿瘤。其中比较恶性的DIPG,主要发生在儿童时期的腹侧脑桥部位[1,2],总体中位生存期为9至11个月,两年内存活率不到10%[3,4],因此目前DIPG已经成为儿童最致命的疾病之一。DIPG第一个发病高峰在6-7岁[5],第二个发病高峰为20-50岁(中位年龄34岁)[6]。由于肿瘤的位置和浸润性,不能通过手术进行切除[7];因此目前DIPG的常规治疗是放射治疗,但是它仅仅能使患者的神经系统症状暂时缓解,对总体生存率几乎没有改善[8];而常规化疗药物对此疾病也束手无策。

免疫疗法正迅速成为治疗恶性肿瘤最有希望的临床疗法。历史上中枢神经系统由于被认为不存在淋巴系统,而被认为是免疫特权区[9,10]。然而,最近发现中枢神经系统中依然存在着淋巴系统[11],这导致了对肿瘤细胞逃避免疫系统监控机制的新见解,引起DIPG等脑癌免疫治疗研究的高潮。DIPG或是GBM免疫治疗的核心是找到肿瘤特异性表达的抗原。肿瘤抗原是由基因突变的癌细胞产生的结构异常和功能异常的蛋白质片段,但这些突变蛋白许多都与正常蛋白十分相似,使得自身的免疫系统无法识别它们。EGFR变异体III (EGFRvIII)是神经母胶质瘤中最常见的突变之一。目前已经有靶向EGFRvIII的GBM一期免疫疫苗疗法[12,13]。经研究,EGFRvIII也被发现在近50%的DIPG/GBM患者中高表达,表明这个靶点也适用于DIPG/GBM的免疫治疗[14]。

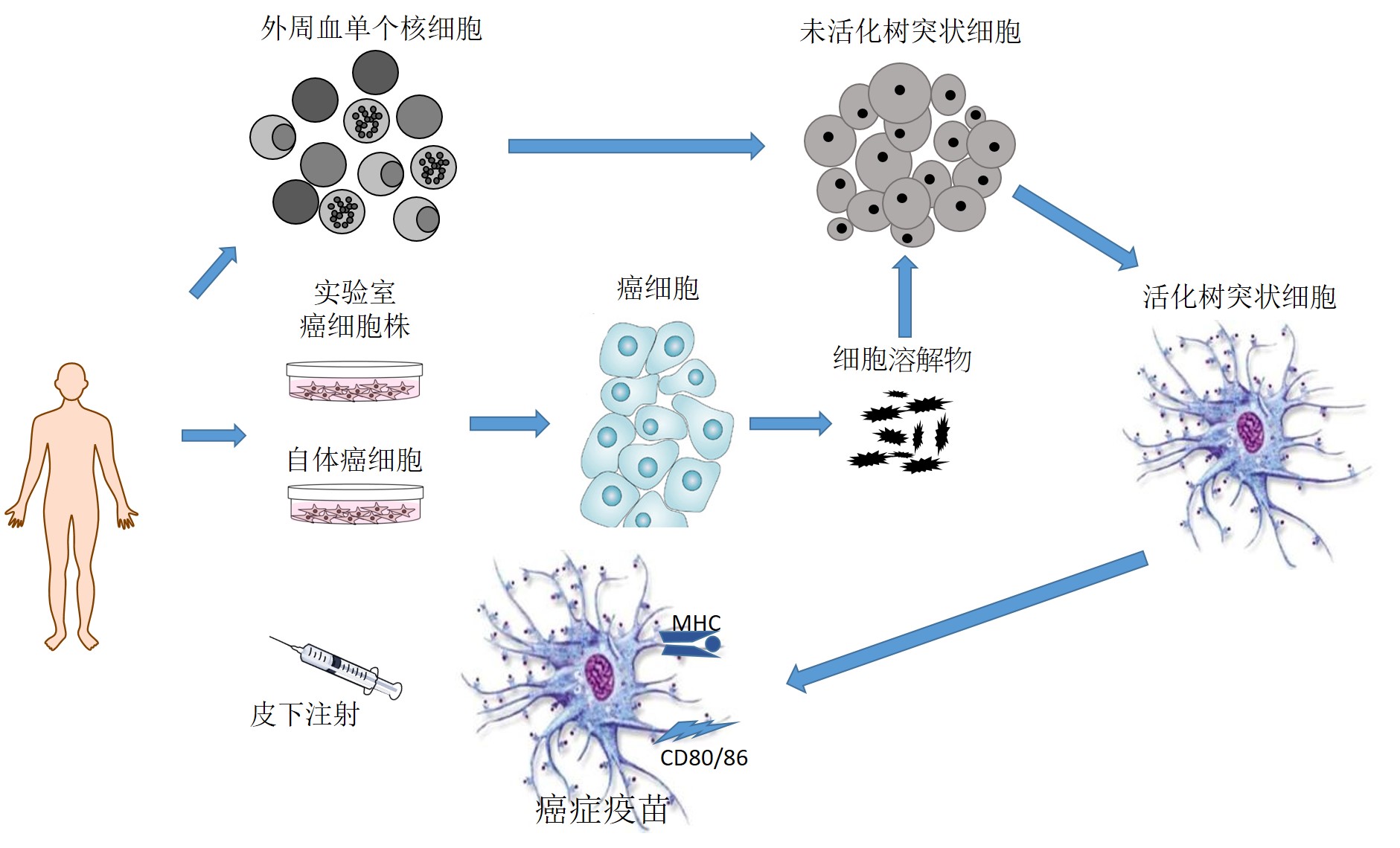

这些研究表明脑癌患者可以从免疫治疗中获益。然而,抗体(pd-1)或其配体(pd-l1)抑制肿瘤免疫逃逸的结果相当有限,平均有效率为10-15%的患者中观察到疾病控制。其他重要的免疫障碍包括T调节(Treg)细胞导致的免疫耐受性,以及各种降低肿瘤中效应T细胞功能的可溶性或细胞表面免疫抑制配体。另一种能引起T细胞反应的免疫疗法是疫苗接种。疫苗可在体内反应扩大肿瘤特异性T细胞,成为联合免疫治疗提供重要的合作细胞。然而,癌症疫苗的预期潜力尚未在临床环境中实现。在某种程度上,这可能与抗原的选择有关:迄今为止,大多数的肿瘤疫苗都使用了单一的肿瘤抗原。使用多种肿瘤特定性抗原,如自身肿瘤溶解后提呈多样抗原,或由肿瘤突变引起的新表位抗原,是一种很有前途的肿瘤疫苗接种方法。

各种免疫调节治疗的组合将需要适当地调动免疫,充分利用脑癌的天然免疫原性。接下来需要更进一步的评估这些癌症疫苗治疗DIPG的安全性和有效性。

参考文献

[2]Helton, K. J., Weeks, J. K., Phillips, N. S., Zou, P., Kun, L. E., Khan, R. B., et al.(2008). Diffusion tensor imaging of brainstem tumors: axonal degeneration of motor and sensory tracts. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 1, 270–276.

[3]Cooney T, Lane A, Bartels U, Bouffet E, Goldman S et al (2017) Contemporary survival endpoints: an international diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma registry study. Neuro-Oncology 19:1279–1280.

[6]Rineer, J., Schreiber, D., Choi, K., and Rotman, M. (2010). Characterization and outcomes of infratentorial malignant glioma: a population-based study using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End-Results database. Radiother

[9]Carson, M. J., Doose, J. M., Melchior, B., Schmid, C. D., and Ploix, C. C. (2006).CNS immune privilege: hiding in plain sight. Immunol. Rev. 213, 48–65.

[10]Vauleon, E., Avril, T., Collet, B., Mosser, J., and Quillien, V. (2010). Overview of cellular immunotherapy for patients with glioblastoma. Clin. Dev. Immunol.2010:18.

[11]Louveau, A., Smirnov, I., Keyes, T. J., Eccles, J. D., Rouhani, S. J., Peske, J. D., et al.(2015). Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523, 337–341.

[12]Li, G., Mitra, S., and Wong, A. J. (2010). The epidermal growth factor variant III peptide vaccine for treatment of malignant gliomas. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 21,87–93

[13]Staedtke, V., Bai, R. Y., and Laterra, J. (2016). Investigational new drugs for brain cancer. Exp. Opin. Investig. Drugs 25, 937–956.

[14]Li, G., Mitra, S. S., Monje, M., Henrich, K. N., Bangs, C. D., Nitta, R. T., et al. (2012).Expression of epidermal growth factor variant III (EGFRvIII) in pediatricdiffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 108, 395–402.